They told me that trying to open the largest archive of inaccessible Holocaust-related documents would be like tilting at windmills….Too much resistance, too little compassion.

In 1998, shortly after joining the staff of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I was invited to a meeting with the director of the International Tracing Service (ITS). The director had come to Washington in hopes of copying some archival collections I had helped the Museum acquire. When he was asked about access to ITS's massive and secretive Holocaust-era collections, he reported that the International Commission of ITS had decided in principle to open the ITS archives-but not for three to five years, the estimated time required to make digital copies of the millions of documents in its possession. The director declined further discussion.

Another five years to see documents already hidden from the public for more than half a century? That made no sense. Archives in Eastern Europe and the former USSR had opened their doors after the fall of Communism; restrictions governing national archives had been lifted in Western Europe as well. While I was not responsible for the Museum's archival collection activity, this "special case" bothered me. I began to gather information.

ITS, located in Bad Arolsen, Germany, held the largest collection of inaccessible records anywhere that shed light on the fates of people from across Europe-people of virtually every European nationality who were targeted and suffered at the hands of the Nazis. Allied forces had collected the documents as they liberated camps and forced labor sites and during the postwar occupation of Germany and Austria. ITS also held the records of displaced persons camps run by the Allies, and thousands of additional collections deposited there right up to 2006. Sometimes documents were sent to ITS precisely because governments knew that at Bad Arolsen no one would ever see them.

How these records came to rest in Bad Arolsen is itself part of a terrible history. Located in a rural region, the town was not heavily bombed during the war. Arolsen housed an extensive SS training facility, thanks to the involvement of Josias, Prince of Waldeck, the SS Obergruppenfuhrer in the region, whose family's ancestral residence was (and is) in the town. Having an SS facility was good for the local economy, though fatal for the community's Jews. As Allied forces approached, the empty SS buildings were a convenient place to dump documents. Six decades later-after passing in 1955 from management by the Allied High Commission for Germany to management by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)-at least 50 million Holocaust-related documents dealing with the fates of more than 17 million people were still hidden away there, under lock and key.

How could ITS's governing body-an International Commission of eleven democratic governments (nine from Europe plus the United States and Israel) and the ICRC (in charge of day-to-day operations)-justify keeping this documentation beyond the reach of scholars? Worse, how could they deprive aging survivors of their family records and the comfort of knowing that the documentary record of what had happened to them and their families would not be "swept under the rug," as one survivor expressed it to me, once the survivor generation was gone? Survivor volunteers at the Holocaust Museum told me they'd been "waiting for information from the Red Cross for years." They asked for help. Everyone else told me I'd be tilting at windmills.

Getting Involved

In May 2001 I decided to attend the annual meeting of the International Commission in Paris. Representation from all countries was low-level, and the meeting was low-energy. I made a plea that release of the ITS documents should not follow a diplomat's or an archivist's timetable, but had to be dictated by the actuarial table of the survivor generation. My appeal was ignored.

The Commission was bogged down in debate about "access guidelines," and the guidelines they were considering were upsetting. Advance application would be required, with no time limit for receiving a response. No access would be granted if ITS decided that the applicant should look for answers elsewhere. Neither researchers nor survivors would see finding aids. Scholars would have to pay for staff assistance and buy indemnity insurance for ITS, the ICRC, and the Commission's eleven governments in case of a claim of document misuse. These guidelines virtually guaranteed that no one would seek or gain entry.

If anyone did, a last trap would await them. The ICRC insisted that all information in the documents relating to persons, places, or dates be "anonymized"-that is, blacked out.

No decisions on access guidelines or a timetable were reached in Paris, and the Commission put off further discussion until its May 2002 meeting in Berlin.

That winter I visited Bad Arolsen together with the U.S. embassy officer who served on the Commission. The welcome was as icy as the weather. The director ushered us into a conference room near the entrance…and near the exit. Referring to the Bonn Accords of 1955 that governed ITS operations as well as ICRC prerogatives, he indicated that he would not permit us to inspect the archival collections during the visit.

The director brought several ITS staff into the room to provide information. (Later, one confided to me that staffers had been instructed not to answer questions.) Once the staff was ushered out, the director, sensing our anger, agreed to let us see the digital imaging equipment used to copy the documents.

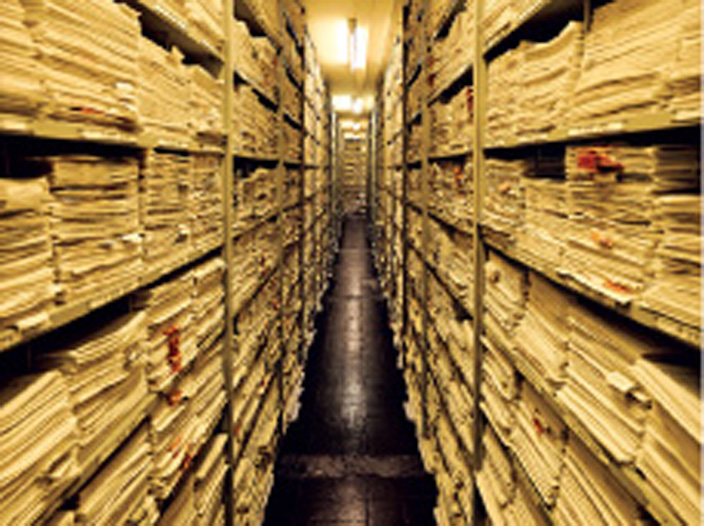

That was a mistake! I dove into the stack of documents being copied, saw registers of collections already reproduced, and solicited answers from the technicians about the process. What would be copied next? That question required a collection manager to answer, and when the director was called away to his next meeting-evidently ours was supposed to be short-the collection manager took us into the storage deposits. I was overwhelmed by rooms stacked floor to ceiling with documentation of transports, deportations, concentration camps, Gestapo offices, forced and slave labor sites, displaced persons camps, and resettlement files relating to millions of innocent victims of the Nazis and their Axis allies. I also got a quick tutorial in how the staff treated a survivor's request for information: Every request passed through 17 separate work stations, and upon arrival at each station the inquiry would be placed at the bottom of the pile. I began to understand why survivors were kept waiting for years!

But there were other factors as well. Before the visit, I had obtained a bootleg copy of the documentary film "Biedermann's Reich," which had been shown in Germany in 1999 but then withdrawn, apparently as a result of ICRC legal action. The film showed an elderly Ukrainian, a former forced laborer, who tried for years to obtain documentation from ITS about his wartime victimization by the Nazi regime. Only when an investigative journalist appeared at ITS headquarters to take up the Ukrainian's cause did a serious search take place. The documents for which the visibly suffering old man had waited nearly a decade were found in under an hour. The film indicated that the staffer who helped the journalist was reprimanded and then forced out of her job by ITS director Charles Biedermann.

When we rejoined the director for coffee, my embassy colleague asked about the handling of survivor requests. Biedermann replied coolly that ITS had a backlog of 450,000 requests, each of which had to go through 17 stations. The sense of urgency I felt was nowhere to be seen. It was the process, not the people, that mattered!

I left Bad Arolsen determined to convince the International Commission to take action, but how? Each member served for just a year or two, and the Commission met only once a year. Without strong motivation, they would surely do nothing and wait to be rotated off.

Perhaps the Commission would be moved, as I had been, by learning about the powerful contents of the archive. I requested inventories of ITS's holdings-and met a stone wall. At the Commission's May 2002 meeting in Berlin, the chair (from Germany that year) chastised me publicly for requesting "restricted" information. Lists of collections would be provided to Commission members only after a unanimous request by all eleven countries-and that, he stated with self-assurance, would not happen. The director, meanwhile, let some Commission members know that if they supported my request, he would see to an even slower flow of responses to their country's survivors.

Over lunch, a German diplomat confided that Germany, which had been funding ITS under terms of a postwar agreement, wanted to assert national control and apply German privacy law to the ITS collections. If that failed, Germany intended to keep the archive closed by provoking legal conflicts among Commission countries over privacy regulations that would drag on for years.

In 2003, the Commission met for half a day in Athens. No progress. I stayed away, gathering information, exploring precedents, looking for new strategies.

Before the International Commission's June 2004 meeting in Jerusalem, I pressed the U.S. State Department, America's formal representative on the Commission, to adopt a more aggressive stance, to no avail. When I proposed that the State Department might hint at a possible reduction in America's sizeable contribution to the ICRC's budget and suggest that, if no progress were made, we consider withdrawing from ITS the millions of documents deposited there by American military forces, I was accused of wanting to "toss a bomb onto the negotiating table." I was told that the official stance of the United States was to hope that some other country might press the access issue!

I had no bomb to toss, only a pen. On Memorial Day weekend in 2004, as the new World War II Memorial was being dedicated in Washington, I wrote in protest to the State Department expressing my belief that the American failure to act was "…cementing the place of our own country as part of the problem rather than part of the solution….In the face of a dying generation of World War II veterans…the United States [has] opened the earth and dedicates a granite monument….In the face of a dying generation of Holocaust survivors, who suffered the full fury of the Nazis and their allies, we are unable to…lay open a pile of paper that tells their story….This will not be a chapter of Holocaust history we will be proud to teach to future generations of Americans."

I enlisted Ben Meed, president of the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors and a Warsaw ghetto survivor, to write a strongly worded letter to the International Commission demanding access. The president of the German Studies Association of the United States, Henry Friedlander, a survivor of the Lodz ghetto, did the same. But neither the voices of these survivors nor my own made an impact.

Was there another world forum that might prove more responsive?

International Task Force

In December 2003, the twenty-country International Task Force on Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research met in Washington, D.C. Created on the initiative of Swedish Prime Minister Goran Persson, Task Force members were committed to principles enunciated in the Stockholm Declaration of 2000. One called for open access to Holocaust-related archives.

At the final plenary I raised the ITS access issue.

To break the logjam over conflicting national privacy laws, and to bring the ITS documentation closer to survivors and other potential users, I proposed for the first time publicly that copies of the entire archive be placed at Holocaust research centers in the eleven International Commission member states and be made accessible under the respective national laws and privacy practices.

The Task Force chair, from the U.S. State Department, ruled my intervention inappropriate because ITS was not on the agenda, but many NGO representatives at the meeting expressed interest in learning more. Moreover, nine of the eleven countries on the ITS International Commission were members of the Task Force and thus committed, through the Stockholm Declaration, to open access to Holocaust-related archives. Could these states commit to openness in the Task Force and at the same time obstruct access in the ITS Commission? This was an angle worth pursuing.

For the International Task Force's June 2004 meeting in Rome, I wrote a "white paper" which described the contents of the ITS archive and explained the systematic evasion of decision-making responsibility that resulted from the arcane set of relationships among the International Commission, the German Interior Ministry (which funds ITS), the ITS director (an ICRC employee), and the ICRC in Geneva. Describing the massive backlog of unanswered survivor requests, I urged immediate Task Force involvement.

The head of the U.S. delegation to the Task Force, who had already accused me of wanting to "toss bombs," disavowed the "white paper" because it had not been-and he assured me would not have been-cleared in advance, but participants picked up 150 copies the first day and even more on day two. On day three, Task Force members passed a unanimous resolution calling for the immediate opening of the ITS archives! Task Force representatives followed the resolution with a visit to Bad Arolsen, where they experienced firsthand ITS's "closed-door, share-no-information" policy. I gained allies, and two additional Task Force resolutions followed.

With these resolutions in hand, I could turn to the media.

Going Public

In May 2005, just before the International Commission gathered in Rome, a longtime friend and fellow synagogue member at Temple Rodef Shalom in Falls Church, Virginia wrote an article, "Pressure Mounts to Open Holocaust Records," for the Minneapolis Star Tribune which was syndicated online and to outlets across the U.S. That same month, a German writer with whom I'd been in touch blasted ITS as a "bureaucratic dinosaur" in the influential German newspaper Die Zeit, while hailing ITS's archival holdings as a monument at least equal in importance to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe that was about to be dedicated in Berlin. Die Zeit also published a lead editorial calling the ITS situation a "scandal."

The warning was clear: If the ITS problem were not solved, the Berlin memorial, in which the German government was so heavily invested both financially and symbolically, might open amid controversy.

Two weeks later, it was clear that this strategy was having an impact: The 2005 International Commission meeting in Rome was fraught with complaints about the public scrutiny, vehement arguments, and unscheduled recesses to allow tempers to cool and strategies to be reconsidered. Still, Germany, Italy, and Belgium, supported by the ICRC and the ITS director, insisted on unanimity for any decision, and asserted they would not endorse a decision to act. When the Italian chair refused to call a vote, stating that nothing less than full consensus would be "legitimate," six countries joined together to authorize creation of a committee of experts, with each country allowed to select its own participants. With the chair still insisting that the move was "illegitimate," dates were set for the expert committee's first meeting, to take place in Paris.

Finally, a majority view had prevailed over the stranglehold applied in the name of "diplomatic consensus."

The New Committee

The "committee of experts," comprised of Commission diplomats, expert archivists, and historians, gathered in Paris-and intense discussions ensued. Opponents of opening the archives employed heavy-handed tactics designed to derail the effort by getting me to back away. They asked me: "Do you really want it to be known that some Jews 'collaborated' with the Nazis in camps and ghettos?" I retorted: "It is well known that Jews were placed in impossible situations by their murderers and sometimes acted in ways that we, in hindsight and not threatened as they were, might question, but there is no question of who the real perpetrators were during the Shoah. Any effort to transform the victims into 'perpetrators' is morally abhorrent, bordering on Holocaust denial."

One of the experts from the German Ministry of Interior finally asked the question I'd been anticipating since that warning in Berlin in 2002: "What right does anyone but Germany have to the ITS documents, since German authorities created the records?" I responded with lines I had rehearsed in my head for some time: "First, half of the documents are of Allied provenance from the postwar period, thus outside German claim. Second, the Nazi documents of German provenance are not German property in my view, but 'war booty' captured from a regime that had unleashed and lost a murderous war of aggression. Morally the documents belong to the victims and their families, certainly not to the perpetrators." And finally (I knew this was make or break), I noted: "This claim to ownership of the records constitutes, to my knowledge, the first time in any forum that a representative of Germany has asserted a claim to 'privileged status' based on direct descent of the Federal Republic from the Third Reich."

These exchanges made me more aware of the German Ministry of Interior's insensitivity to the moral imperative of opening ITS and drove home as well the political risk to Germany posed by such recalcitrance. Going forward I knew I would have to find and engage more sensitive interlocutors in Germany's government.

Still, the stage was set for the committee of experts to get to work. During lengthy meetings in Paris, Bad Arolsen, and The Hague, the committee reached consensus on recommendations it would forward to the International Commission. In the end, the experts even agreed to support my proposal to allow the distribution of copies of ITS's archives to Holocaust research centers in the Commission nations.

What remained was convincing the countries on the International Commission and the ICRC to accept the recommendations. Momentum appeared to be shifting my way, but opposition from the ITS director and the ICRC was still fierce, and some countries appeared determined to force further delay, even as increasing numbers of Holocaust survivors disappeared before their eyes. The actuarial table was taking its deadly toll, and I knew it was time for the end-game.

Ups and Downs

In Washington, with survivors from Florida to California now voicing their support, I signaled the leadership of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum that the time had come to throw the full weight of the institution into what I asserted would be a final push. Assistant Secretary of State Nicholas Burns agreed to be briefed. In a meeting in his office on the seventh floor of the U.S. State Department, attended by Museum Director Sara Bloomfield, myself, and the Museum's Director of Communications Arthur Berger, Burns assured us-with the Department's Special Ambassador for Holocaust Issues, who had represented the Department on ITS matters since 2003, hearing the message as well-that from then on we would get full State Department support.

I was making progress in expanding relationships in Berlin as well. When the German Minister of Justice, Brigitte Zypries, made a protocol visit to our Museum in 2004, I had raised the ITS problem and found that she was open to hearing my arguments, though the issue was, as she put it, "outside of her official purview." I remained in touch with her office, sent regular updates to her chief of staff, and, when Sara Bloomfield was invited in 2005 to the dedication of Germany's new Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, arranged for her to meet with Minister Zypries.

The opposition, meanwhile, remained vocal, and some attacks were personal. In January 2006, a commentary on the ITS website, written in-house, labeled the push to open the archives "unjustifiable…both legally and morally." Shortly afterward, in an article titled "Not the Biggest Holocaust Archive in the World" published in the German journal Tribune, a leading German Holocaust scholar with close ties to the ITS director accused me of working with a "crowbar" and a "club" and denounced the U.S. for taking an interest in what was a "European affair." He followed up with broadcast interviews.

Having witnessed the International Commission's sensitivity to public scrutiny, I was encouraged that the media again became part of the battleground.

Award-winning German filmmaker Christine Ruetten worked with me on a documentary report juxtaposing the recalcitrant ITS director with a survivor longing "to know the truth" and representatives of the German Jewish community decrying the inaccessibility of ITS's Holocaust collections. In March 2006, the piece aired repeatedly throughout the country on Germany's equivalent to 60 Minutes. The producers raised the possibility that the archive was closed not out of concern for Holocaust victims' privacy, but because ITS was shielding the names of Holocaust perpetrators. On camera I made the (unauthorized) assertion that the United States would not allow the last remnant of the Holocaust survivor generation to pass away without giving these survivors access to ITS records. I also suggested that, with Holocaust denial on the rise, 50 million documents might provide an effective antidote to the rantings of Iranian President Ahmedinajad. And I concluded that "it is generally acknowledged that knowingly concealing the documentation of the Holocaust is itself a form of Holocaust denial."

By this time, I was maintaining direct contact with each country on the International Commission. France, Luxemburg, Greece, the U.K., and the Netherlands indicated their willingness to support opening the archives. I met with the Belgian ambassador to Washington and gained his commitment to try to change Belgium's stance-which he did! I visited the mayor of Rome, who was planning a new Holocaust museum in his city; he agreed to launch a formal inquiry into the Italian government's policy. Poland adopted a waiting stance. And the Israeli government, informed erroneously that Yad Vashem already had copies of all ITS records that might be of interest to Israel (Yad Vashem had microfilmed some ITS documentation in the 1950s), remained silent, hesitating to engage in a dispute with its close partner Germany, especially since the U.S. was already forcefully pressing the case.

As the May 2006 International Commission meeting in Luxemburg approached, the Museum launched a press campaign focusing on the remaining pockets of resistance.

A February 20 article in the New York Times describing a "U.S.-German flare-up" quoted Sara Bloomfield's statement that the German response to the ITS archive issue was "a big scar on the image of Germany," and included my declaration that "hiding this record is a form of Holocaust denial." The story-picked up and reprinted worldwide-generated an angry response from the German Embassy, but also resulted in my having near-daily conversations with the embassy's political counselor and high-level access in the German Foreign Ministry. (Both the new German Ambassador in Washington Klaus Scharioth and the Foreign Ministry's Legal and Holocaust Affairs Divisions would later help to resolve issues that the German Interior Ministry considered insurmountable.)

On March 7, the Museum issued a press release calling on the ICRC and the ITS director to end their systematic opposition to opening the archive. The initial ICRC response was hostile, but the ICRC's president, Dr. Jakob Kellenberger, flew from Geneva to Washington and met with director Bloomfield. When the chief ICRC representative in Luxemburg nearly scuttled that decisive meeting weeks later, immediate contact between Sara Bloomfield's office and Dr. Kellenberger's, with support from the U.S. State Department's representative on the Commission, saved the day.

On March 25, a Washington Post editorial accused the ITS director of "conspiring" with the German Interior Ministry to block progress, and on April 18 the newspaper published a follow-up article predicting that a "political brawl" might develop in Luxemburg. At the same time, a privately-sponsored online petition advocating open access to the ITS archives quickly drew more than 4,000 signatures and supportive comments from around the world.

Denouement

As agreement to open the archives became increasingly likely, the ITS director searched for legal obstacles to undercut the committee of experts' recommendations. When the Commission refused to accept "independent" rulings from ITS's own lawyers and the Interior Ministry, he turned to the German Ministry of Justice. This was just the opening-the route to getting officially involved-that Minister Zypries needed, and with principle and compassion, she made use of it.

At the request of her chief of staff, and with the media barrage in full swing, I provided the minister with a briefing paper explaining the recommendations of the experts committee. Within days, Minister Zypries took the matter to an interministerial meeting of Germany's new cabinet (Angela Merkel had replaced Gerhard Schroeder as chancellor) and convinced her colleagues that German policy had to change. Shortly thereafter, on April 18, 2006, she visited Washington and announced from the stage of our Museum's Helena Rubinstein Auditorium that Germany would support the opening of the International Tracing Service archives.

After a last-minute ICRC attempt to derail the agreement failed, on May 16, 2006 all eleven International Commission member states plus the ICRC initialed agreements in Luxemburg stipulating that, once the agreements were ratified by the states, the archives would be opened. When the ITS director refused to take steps to prepare for the change, the ICRC released him from his post.

Ratification required one final assault.

As a condition of their agreement to open the archives, some countries had insisted that the Bonn Accords of 1955, which governed ITS operations, would have to be formally amended. They projected it could take up to five years to complete the ratification of the amendments initialed in Luxemburg. So we continued the media pressure, and I testified before the Subcommittee on Europe of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, prompting prominent members of Congress to write letters to the ambassadors of Commission countries in Washington and to their parliamentary counterparts abroad. As a result, the ratification period was shortened to eighteen months.

Finally! On November 28, 2007, the last of the eleven countries on the International Commission completed the ratification process. The ICRC then agreed to implement the decision.

Today

So far, more than 100 million digital images of ITS documents have been transferred to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, to Yad Vashem in Israel, and to repositories in Poland and Luxemburg. Other Commission countries are still deciding whether to take the copies and where to place them. Individuals can access the material directly at any of these national repositories or at ITS Bad Arolsen (see "Researching Family Holocaust History").

While the total document count in the ITS archives will only be determined as the digital scanning process continues, we know there are approximately 13.5 million concentration camp documents, transport and deportation lists, Gestapo arrest records, and prison records; more than 10 million pages of forced and slave labor documentation; more than 3.2 million original displaced persons ID cards; and 450,000+ displaced persons case files, plus resettlement documents and emigration records, totaling more than 15 million pages. The collection also includes Gestapo order files, cemetery records for deceased prisoners and forced laborers, concentration camp prisoner testimonies taken by liberating forces, and more than 2.5 million postwar inquiry and correspondence files, which are themselves rich sources of historical information.

Some of the collections are massive: 101,063 Gestapo arrest records from the city of Koblenz, for example. Others are tiny, but poignant, such as the list one of Oskar Schindler's Jews typed to record the arrival of the 700 men and 300 women Schindler saved at his factory in Brunnlitz. There are also files on perpetrators (such as John Demjanjuk, now on trial in Germany) who abused the displaced persons system to come to the U.S. in an attempt to escape prosecution.

Often, these millions of documents reveal not grand strategy, as history is generally written, but the grinding routine of man's inhumanity to man, of a prisoner's efforts to survive just one more day, of perpetrator calculations regarding how to reap the most benefit from the "disposable" human assets consigned to his control. This documentation will serve survivors and memory in many unique ways. Future scholars and educators will be able to place individual fates in the context of broader historical events and teach powerful lessons that humankind can never afford to forget.

To date the Museum has fielded 8,000+ inquiries from survivors and their families. Locating information within these huge collections remains a challenge. For some people the documentation provides no answers. But in other cases, family members have discovered relatives long presumed dead. In other instances, the documents reveal unknown details of an individual's Holocaust experience. In still others, learning a date of death has enabled survivors to say Kaddish-after 60 years-on the actual yahrzeit of a lost loved one.

Do I consider the opening of ITS a "victory"? The battle was long and hard, so yes, it was a victory of sorts. But it was unnecessarily long in coming, and came too late for many survivors who died without receiving answers. As in so many other respects, the survivors deserved better than what the world gave them.