Introduction

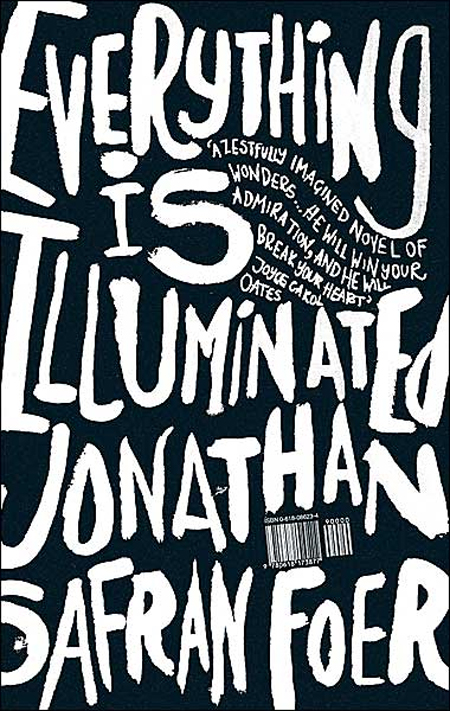

Prior to its publication in Spring 2002, an excerpt of Everything Is Illuminated appeared in the New Yorker'sdebut-fiction issue. As a result of this exposure, both Jonathan Safran Foer, the author and a recent Princeton graduate, and his first novel received tremendous attention and, ultimately, critical acclaim.

What makes this novel so notable? For starters, Foer was only 24 years old when his book was published, a remarkable accomplishment for so young a person. He also chose to give one of his main characters his own name and had the character embark on a journey that he himself had just completed. This is a device that serves well one of the themes of the book, i.e. the rift between what is and what seems to be.

And, if not breaking new ground, this book treads into some new areas where, perhaps, only a young author can safely travel. This book certainly qualifies as Holocaust literature in that it is about a young Jewish adult's search to understand what happened to his grandfather, whom he had never met, during the Holocaust. However, this is Holocaust literature with a twist, with a Generation X's sensibility. Foer deftly weaves together silly humor, quaint storytelling and unique characters into a narrative that is both irreverent and intriguing at the same time.

Using this Discussion Guide

The book's publisher, Houghton Mifflin Books, has posted online an extensive discussion guide, background about the author and a conversation with the author. This can be found on the publisher's website.

Though Foer does reveal, in the online interview, how being Jewish played into how he came to write this book, the otherwise excellent accompanying discussion guide does not address questions of particular Jewish interest. Therefore, this UAHC discussion guide will presume the user is has already read through the publisher's guide and is using this guide as a supplement. Feel free to pick and choose between the two in order to address the aspects of the book that most interest you.

Discussion Questions Based on the Online "Questions for Discussion"

- At the beginning of the book Alex, the guide, has a difficult time understanding why Jews from America would spend a lot of money to track down their ancestors' shtetls in Ukraine and Poland. What do we learn about Alex from his question? What do you think might be some of the motivations for American Jews to visit the shtetls of their grandparents and great-grandparents? In what ways do you think this is related to an increased interest, in general, in genealogy?

- Separated by time and space from the "old country" of Eastern Europe, in what ways do American Jews strive to fill in the gap between what we know and what we wish we knew about actual people who lived there and the events of their lives? What do you imagine this gap will be like for succeeding generations of American Jews?

- On page 227, Alex's grandfather says, "I am not a bad person. I am a good person who has lived in a bad time." To what extent can you accept this explanation for his inaction during the Holocaust? In what ways is he speaking for Holocaust-era shtetl residents all over Europe? To what extent do you agree with Alex's grandfather when he says, "You would not help somebody if it signified that you would be murdered and your family would be murdered?"

- The online guide asks, "How do the characters in Everything Is Illuminated live their lives in the wake of tragic events? How do we both move on and still remember these events? What roles to stories play in reconciling ourselves with the past?"

How might you answer these questions if you were a Holocaust survivor? A child of a survivor? Three generations removed from the Holocaust? In what ways do you see the collective American Jewish community struggle with these same questions?

Discussion Questions Based on the Online Conversation with Jonathan Safran Foer

- In the interview, we learn that the author did not, initially, set out to write a novel. Instead, he intended to chronicle a trip he was making at age 20 to Ukraine to learn about the woman he was told had saved his grandfather from the Nazis. However, he went unprepared and, consequently, did not get his questions answered. Nonetheless, he went on to write a book that created a story that imaginatively answered his questions, one "[that allowed him] to wander, to invent, to use what I had seen as a canvas, rather than the paints." How to you feel about writers using the Holocaust as a backdrop for historical fiction? To what extent are you concerned about what is written being "true" to the facts? To what extent are you particularly vigilant about how people of that time and their feelings are described? How might your answers to these questions vary depending on your age?

- In the interview, Foer says "I didn't tell my grandmother about the trip-she would never have let me go?" We don't know much about Foer from this interview and we know even less about his grandmother. Nonetheless, what reasons do you think a grandparent might have to discourage a grandchild from uncovering the past? Which of those reasons might be in the best interest of the grandparent? In the best interests off the grandchild?

- In the interview, Foer states "The Holocaust presents a real moral quandary for the artist." He goes on to question if there are limits to using humor, quaintness and sentimentality in an attempt to get at the truth. He concludes by asking, "What, if anything, is untouchable?" What limits, if any, do you think there should be on how the Holocaust is represented in the arts? Why? (As an example, you might want to think about the Spring 2002 Holocaust art exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York entitled "Mirroring Evil" that included a Lego concentration camp and a doctored photo of a healthy looking concentration camp prisoner-actually the artist--holding a can of Diet Coke while standing among other emaciated prisoners.)

- In the Talmud, the rabbis engage in a discussion about whether study or action is of greater value. Instead of seeing it as an either/or question, Rabbi Akiva suggests there is interplay between the two. Compare this thought to two others from the interview: Foer describes his book as "a quixotic misadventure?which culminates in the most essential existential questions: Who am I? What am I to do?"As a new writer who was Jewish and embarking on an ill-planned fact-finding mission to Ukraine, Foer describes his state of mind: "There was a split-a strange and exhilarating split-between the Jonathan thatthought (secular) and the Jonathan that did (Jewish)."

- Comparing Rabbi Akiva's answer to Foer's statements, what do you see is the relationship between, on the one hand, study, thought and the existential question "Who am I?" and, on the other hand, action, doing and the question "What am I to do?"

- In what ways have you experienced the same kind of secular/Jewish "split" Foer claims exists for him between thinking secular) and doing (Jewish)?

Susan Kittner Huntting is the Religious School Director at Temple Sinai in Sarasota, Florida.