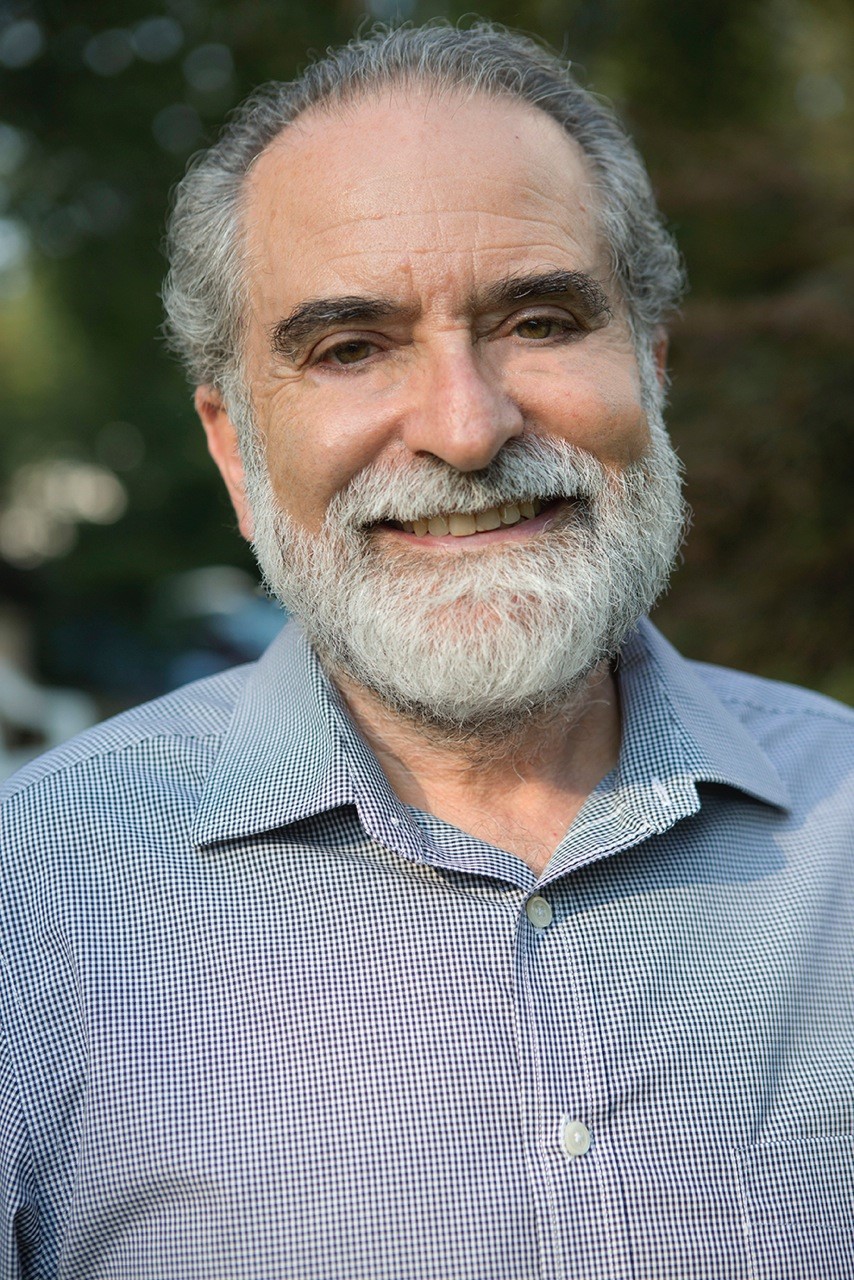

This year marks the 400th anniversary of the death of playwright William Shakespeare, yet doubt remains about the authorship of the plays attributed to him. Some believe that a Jewish woman – Aemelia Bassano – is the true playwright. I asked Canadian journalist and author Michael Posner to lay out the evidence for this claim.

ReformJudaism.org: Why is authorship of Shakespeare’s plays still an issue in some circles?

Michael Posner: Verifiable facts of Shakespeare’s life are few. He acted in two of English playwright Ben Jonson’s plays, owned shares of the Globe Theatre and the Blackfriars, sued people for petty sums, and bought land in Stratford.

It remains a mystery, though, how he acquired his knowledge of foreign languages, where he developed dramatic mastery of the Elizabethan law, the royal court, mathematics, medicine, falconry, astronomy, and the military – to which he had no known exposure. And why did he leave a last will and testament that made no mention of anything he wrote?

His name appeared on many of the plays, but no evidence demonstrates that he actually wrote them. In his diary, Jonson noted that although Shakespeare passed manuscripts of plays to the actors, who in their “ignorance” admired Shakespeare for providing clean copies, he was to be “most faulted” for telling them the copies were his original drafts.

If Shakespeare didn’t write the plays, who did?

The Shakespeare Authorship Trust, which was founded in 1922 “to seek…the truth concerning the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays and poems,” has endorsed about a dozen candidates, among them statesman and essayist Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere (the Earl of Oxford), playwright Christopher Marlowe, and Aemelia Bassano, daughter of a Venetian-born court musician and converso – a Jew who was forced to convert to Christianity but remained secretly Jewish.

What evidence do we have to support the view that Bassano might have written the plays?

The principal proponent of this view, John Hudson – a graduate of the Shakespeare Institute at the University of Birmingham, England – doubts that a man whose works portray strong, well-educated, proto-feminist women would raise his own daughters (as Shakespeare did) as illiterate.

Such portrayals of women are more likely to come from the pen of Aemelia Bassano (1569-1645), a feminist and writer who possessed knowledge that Shakespeare seemingly lacked. In 1611, she distinguished herself as being the first woman to publish a work of original verse in the English language, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Hail God, King of the Jews).

What specific areas of expertise did Bassano possess that Shakespeare supposedly lacked?

Shakespeare’s works contain some 2,000 musical references, many displaying a firm grasp of musical intricacies. Bassano’s 15 closest relatives were professional court musicians, among them Robert Johnson, the most popular musical composer for the plays attributed to Shakespeare.

The playwright had to have known Italian well enough to make elaborate puns and to have read Dante and others in the original language. Bassano likely spoke Italian fluently, as attested to by letters written in Italian from her family to Queen Elizabeth.

In 1592, the very year when the playwright started writing Italian marriage comedies, Bassano left the court – where she had been the longtime mistress of Lord Chamberlain, patron to the very company that mounted the Shakespeare works – and rejoined her family in Italy.

One of Iago’s speeches in Othello describes a distinctive fresco painted on a house in Aemelia’s family hometown of Bassano. Whoever wrote the text must have visited the town, which was not a likely tourist destination.

Are there any Jewish sources in the plays that would support the Bassano authorship theory?

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the Mishnah’s Tractate Nedarim (The Book of Vows) is used to structure how Helena, the daughter of her absent father Nedar (in Hebrew nedar is an adjective that means “missing” or “absent,” and as a noun it means “pledge” or “vow”), compares herself to Hermia. Her criteria – beauty, fairness, and height – are the very same and in the same order as those in the tractate to determine the annulment of marriage vows.

It’s highly unlikely, says Hudson, that the young man from Stratford somehow learned Hebrew and immersed himself in the Talmud.

Did Bassano ever claim to be the playwright?

As women were forbidden to write plays for the stage in Elizabethan England, Bassano may have signaled her claim to authorship by encoding her name in plays. In Othello, Emilia says, “Hark, canst thou hear me? I will play the swan. And die in music. [Singing] willough, willough, willough” (Act V, Scene 2).

The same swan analogy appears in King John, where it is associated with John’s son, and in Merchant of Venice, associated with the character Bassanio. All four names – Emilia, Willough, Johnson, and Bassanio – correspond to her own names: her baptismal name (Aemelia), her mother’s name (Johnson), her adopted name (Willoughby), and her family name (Bassano).

Hudson believes these names were deliberately inserted by Bassano as clues, so that future generations could discover the author’s true identity.

Related Posts

Feminism, Female Protagonists, and Finding Ourselves in Biblical Narratives

Israeli Poems to Get Us Through Times of Fear and Isolation