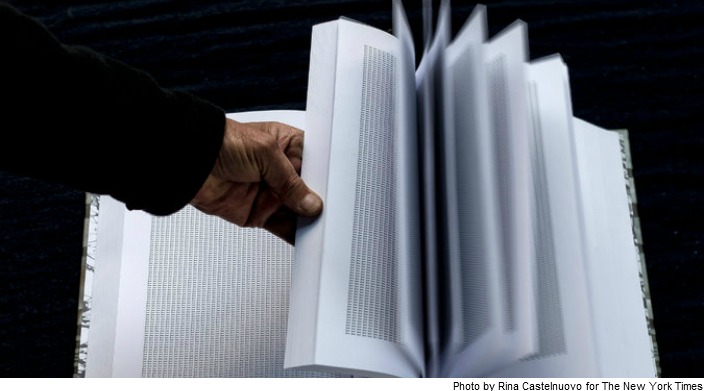

Recently I read about a newly published book that lists every single one of the six million people killed during the Holocaust.

In ascribing the exact same narrow, confining and one-dimensional description – Jew – to each of the six million individuals, the book mimics the Nazis' efforts to implement the Final Solution.

More than reflecting these atrocities, though, does this list – that fills 1,250 pages in stark, empty repetition – truly honor and bless the memory of the six million lost souls?

It is up to us, I believe, to ensure that it does.

As portrayed in Phil Chernofsky's book, their anonymity stands in sharp contrast to Chaim Glasberg, a Czech Holocaust victim whose memory I have carried in my heart for nearly a decade. I first learned of Chaim's life during a visit to Prague's Pinkas Synagogue, one of the first stops on a NFTY L'Dor v'Dor journey on which I was a flight chaperone for a group of teens. As part of the synagogue tour, we each were invited to select an individual – from among the names painted, row upon row upon row, on the sanctuary's stucco-like walls – to carry with us throughout our upcoming week in eastern Europe. As we were leaving the sanctuary, I randomly and hastily plucked Chaim Glasberg's name from the wall, tucking him and all his unknownness into my heart. He has been with me ever since and I do my best to honor and bless his memory.

It is this same honor and blessing that the New York Times' Portraits of Grief bestow upon the 2,606 victims of the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. Unlike Chaim Glasberg and Chernofsky's Jews, though, Tariq Amanullah, Irina Buslo, Mary Teresa Caulfield, Daniel James Shea and the 2,602 others, each of whom is known by name, come vividly to life in the written snapshots of their truncated lives published by the paper in the weeks following their deaths.

It is precisely these spirited sketches of lives cut short that illuminate for me how very deficient Chernofsky's list is as a memorial to six million individual Jews. Without each of us to claim them as our own, they remain nothing but black ink on white paper, empty, nameless words on a page. When we take them into our hearts, however – like Chaim Glasberg – their unknownness fades and we, in our remembering, bestow upon them honor, blessing and, as the poet Zelda has written, "a name…given by our death."

Related Posts

“We Were the Lucky Ones:” Bringing The Holocaust Out of History Books and Into Our Homes

Remembrance and Beyond: International Holocaust Remembrance Day