Many white Jews were raised to believe that America was a kind of promised land, where mass public demonstrations of hatred towards Jews was a thing of the past.

Then came August 12, 2017, the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, VA.

America and the world witnessed a public coming-out ceremony and a call to arms by a coalition of hateful antisemitic militants who for years had been inhabiting dark corners of the web, glorifying and amplifying Jew-hatred as a central ideological pillar.

Having paid little attention to this insidious threat, we were caught by surprise when Klan members and other armed white supremacists converged on our city shouting, “JEWS WILL NOT REPLACE US.” If their purpose was to protest the removal of Civil War hero statues, why did their posters sport swastikas?

Our historic synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel, is located one block from the Stonewall Jackson statue to the east and one block from the Robert E. Lee statue to the west, so we knew we would be at the center of the action on the streets that day.

What would be our response? How would we demonstrate our resistance? We chose to gather in large numbers at our synagogue for our weekly Shabbat prayer service, despite being warned by law enforcement officials that the synagogue could be a target of the alt-right violence.

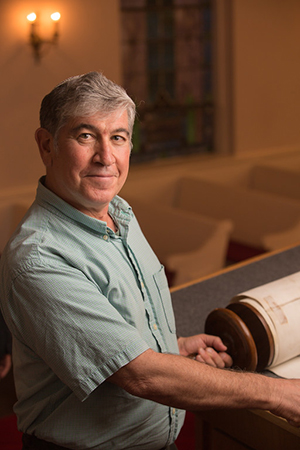

We removed the one item we had in our synagogue that could not be replaced: a rescued Torah scroll that had come from the Jewish community of Frydek-Mistek in the former Czechoslovakia, which we call our “Holocaust Torah.”

We left one Torah scroll in the synagogue because it was our intention to read from it on Shabbat morning, August 12. We did make a change in the time of our services, starting an hour earlier than usual to enable us to all be together for prayers and also be able join the counter demonstrators after services.

For the first time in our synagogue’s 123-year history, we hired a security guard. We had some difficult conversations among ourselves about whether he should be armed and to what extent we would ask this person to put his life in danger to protect our community. We eventually came to the consensus that glass can be repaired, furniture can be purchased, and even ritual objects can be replaced. We therefore decided that we would ask the security person to remain at his post only while people were in the building.

I am proud of the resilience and the courage of so many in our congregation who showed up on August 12, 2017 and who continue to be actively engaged in the struggle against white supremacy. We have reluctantly become accustomed to the presence of various security measures put in pace since that summer, but it has not discouraged people from coming to our building. In fact, our congregation experienced an increase in membership in the year following the summer of 2017.

For me personally, what happened on August 12 was a transformative event. It hit me that while racial hatred has been a constant in the lives People of Color, it has gone essentially unnoticed by the rest of us, including me.

So, I now ask myself shamefully:

Why did I not feel that violence until now?

Was I too complacent, comfortable?

Was I too optimistic about the things I thought were changing for the better?

Why did I not know the history of the statues that are one block away from the synagogue, that I pass every day?

Why did I not have the curiosity to find out?

What else is there that I just do not want to see?

What is at stake in my not seeing?

What will I have to give up in the struggle for change?

My generation of Jews, born after the Holocaust, was raised with the slogan “Never Again,” which in a narrow sense means that Jews must take seriously the words of those who seek to harm us. We have learned that history does not only progress forward; it can go backwards as well.

I now understand this slogan in a more inclusive way. “Never Again” means that after my personal history of being the son of a Holocaust survivor and what all of us here in Charlottesville have experienced, we have a special responsibility to be vigilant about racial and ethnic hatred and injustice wherever we see it

To look for it and ferret it out when we do not see it

To understand clearly how it works, and to look for ways to dismantle it

To be a resister and not a bystander

The Jewish tradition teaches: You are not obligated to complete the task, but neither are you free to desist from it. Each of us must find a way that we can best contribute to this task, and I believe that in solidarity with people of conscience of all faiths, we will all find our way forward together.

Related Posts

Harnessing the Power of our Mothers Around the Seder Table

Melding Tradition and Innovation: Our Interfaith Toddler Naming Ceremony