Rabbi Jack H. Bloom, a practicing psychologist in Connecticut, is director of Professional Career Review for the Central Conference of American Rabbis and editor of Jewish Relational Care A-Z: We Are Our Other's Keeper (The Haworth Press). He was interviewed by the Reform Judaism magazine editors.

You have said that many Jews are "in serious denial about the nature of the Deity with whom we are in relationship."

That's true. Modern commentators do cartwheels to make "difficult" Torah texts consonant with the idea of a benign, perfect Creator of the world who maintains a special, loving, covenantal relationship with the people Israel. One prominent rabbi wrote that "the Torah speaks of God as a parent, a lover, a teacher and an intimate sharer of our hearts."

To the astute reader this is not even close to the whole truth. For many Jews, throughout the ages, God has been and remains a great source of strength and comfort; however, judging from the Torah, our foundation text, all too often God is anything but all-loving.

I could cite any number of Torah passages to prove my point. Here is a less known one: "Now when the Children of Israel were in the wilderness, they found a man picking wood on the Sabbath day. They brought him near…to Moses and to Aaron, and to the entire community; they put him under guard, for it had not been clarified what should be done to him. YHWH said to Moses: 'The man is to be put to death, yes, death, pelt him with stones, the entire community, outside the camp!' So they brought him…outside the camp; they pelted him with stones, so that he died, as YHWH had commanded Moses" (Numbers 15:32).

Not a very loving portrait of God. Even after the passing of time to cool the Divine anger, to perhaps consider compassion, to acknowledge that no law covered this situation, God summarily invokes a law promulgated after the fact and petulantly orders that the entire community stone the unfortunate gatherer. Perplexed by the "apparent severity of the narrative," modern commentators have speculated on God's rationale: "The wood gatherer, therefore, was not just violating one law but was destroying the dream that Israel would be a people obedient to God's ways." But what happened was not apparently severe; it was, in no uncertain terms, a cruel and unforgiving judgment.

Perhaps more familiar to many of us is God's decree pertaining to Yom Kippur observance: "Indeed, any person who does not practice self-denial throughout that day shall be cut off (nichratah) from his kin, and whoever does any work on that day-I will cause that person to perish from among his people" (Lev 23:29-30).

Who would not question a God who treats as capital crimes what we would consider relatively minor infractions-not fasting on Yom Kippur or doing what might be considered "work" according to traditional rabbinic law?

Given that the Torah teaches us that we are created b'tzelem, modeled after God, what are the implications of acknowledging the dark side of God?

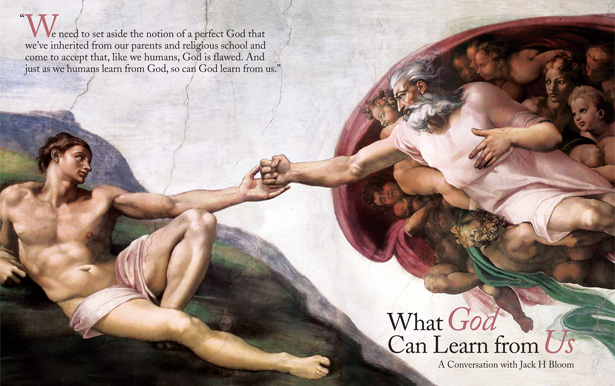

We have long assumed that being so modeled refers to that which is good and noble in us. However, the character traits which cause us discomfort and prompt us to seek out therapy to correct are common to God as well. Just like God, we humans can be intolerant of imperfection (our own and others), judgmental, quick to anger when things don't go our way, and prone to act abusively and destructively. In short, being modeled after God reflects both what is positive and negative about us. To truly grasp this idea, we need to set aside the simplistic concept of a perfect God we've inherited from our parents and religious school teachers and come to see and accept the notion of a flawed or wounded God.

Why do you think this simplistic God concept is so prevalent?

We have what Rabbi Richard Address, director of the Union's Department of Jewish Family Concerns, calls a "pediatric view of divinity"-a view characteristic of young children who see "mom" and "dad" in their roles as parents rather than as complex human beings. As each of us matures, we begin to see our parents for who they are, imperfections and all, and we come to accept that even when they were less than ideal mothers and fathers, they did the best they knew how to do. Our child-parent relationship changes, with our parents learning from us, even as we continue to learn from our parents.

Unfortunately, this kind of transition from an infantile to a mature relationship rarely occurs in our relationship with God. Rather, we stay mired in a less mature, dysfunctional, and ultimately disappointing relationship with the Divine. If instead we recognized that God has imperfections as do our parents, then we could begin to redefine the God-human relationship: just as it is possible for parents to learn from their children, so can God learn from us.

God learn from us? Isn't that an audacious assumption?

Though it may seem audacious to presume that we mere humans can help heal God, this is an essential part of our covenantal relationship. Being in a covenantal relationship offers the possibility of healing in both directions. For both God and humankind, healing occurs in relationship.

But if God is all-knowing and all-sufficient, why would God need to be taught anything by humans?

If God was all-knowing and all-sufficient, why did God feel the need to create humankind? It seems that God was lacking something.

What might that be?

I believe that being the "one and only" made God very lonely. Desirous of companionship, God, with the best of intentions, created a "perfect" world and judged it as "very good." But when faced with issues of competition, rivalry, rejection, and perceived betrayal, God demanded total obedience. When humankind failed to meet God's exacting standards, God became enraged and reacted by cruelly flooding the entire world, almost wiping out all of creation.

The Torah is full of stories about God's fierce anger, rush to judgment, and cruel punishment. God needs to be taught many things, including the difference between obedience and love.

Do you believe that God is teachable?

According to a number of post-biblical Jewish texts, God is indeed teachable. Sometimes God alters behavior and outlook in response to human intervention. For example, Bamidbar Rabbah notes three occasions in which Moses intervenes and God responds: "By your life! You have spoken well! You have taught me. From now on, I will...." After God threatens to punish the Israelites for worshiping the Golden Calf in the wilderness, Moses pleads: "Let not your anger, O YHWH, blaze forth against your people whom You delivered from the land of Egypt with great power and with a mighty hand. Let not the Egyptians say, 'It was with evil intent that He delivered them only to kill them off in the mountains and annihilate them from the face of the earth.' Turn from your flaming anger and renounce the plan to punish Your people! Remember Your servants, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, how You swore to them by Yourself and said to them: 'I will make your offspring as numerous as the stars of the heavens, and I will give to them all this land of which I spoke, to possess forever.' And YHWH renounced the punishment He had planned to bring upon His people" (Exodus 32:14).

But we are not Moses. What can we humans possibly teach God?

God enters into relationship with humanity knowing next to nothing about how to relate. We humans, on the other hand, have a great deal of experience living in relationships. We struggle day-by-day to live with and love others despite their imperfections and our own. We've learned how to build respectful relationships-and we can teach God about what it takes to live peaceably in a relationship with loved ones who do not bend to our will or always live up to our expectations.

We can teach God about self-esteem. God needs constant reassurance. We too often lack faith in ourselves and fall off the balance beam of our equilibrium. Still, after repeated failures, most of us recognize that falling off is inevitable and not a comment on our worth. What counts is getting back on track. We can teach God self-esteem by demonstrating how we move forward despite our reservations and fears. And-when we have learned this lesson ourselves-we can teach God that one doesn't have to trample on others to demonstrate one's self-worth.

We can teach God about forgiveness. God demands repentance (in Hebrew, teshuvah) from humans, but sometimes remains unforgiving of our transgressions unto the third and fourth generation and beyond. We humans, who have spent endless effort and energy practicing repentance, know that the willingness to do teshuvah is a vital aspect of a healthy relationship. We know about searching for what the mystics call nitzotzot kedushah, the "holy sparks" present in and redemptive of all creation.

In addition, we can teach God about the preciousness of human life through the ways we act to preserve and sanctify our lives.

In short, how we as God's partners model ourselves divinely can teach God how to be in the very world that God created.

How do we begin to change our relationship with God?

We start by changing ourselves. In any healthy relationship, when we change, our partner changes. So when we humans become exemplars of what it means to be fully human-often in areas God knows little about-God will have to grow and change, too. In short, by becoming fully human, we help God to become a better exemplar. And that's no small thing. What more could any exemplar-Divine or human-want?