The other day, as I was walking in New York City with my son, I happened to see a couple of young people. They must have been in their early twenties, and were sharply dressed in business suits. As we walked past, I noticed the young woman lighting a cigarette while her friend held a lighter for her.

I couldn’t believe it. How can it be possible in this day and age that a young person would choose to smoke cigarettes? There is incontrovertible evidence that smoking causes all kinds of illness and disease, including cancer. From the time they can watch television, we bombard children with messages about how bad it is to smoke. It’s not as if no one ever told them or showed them the effects of smoking. So, how is it possible that bright, sophisticated young people would ever smoke cigarettes?

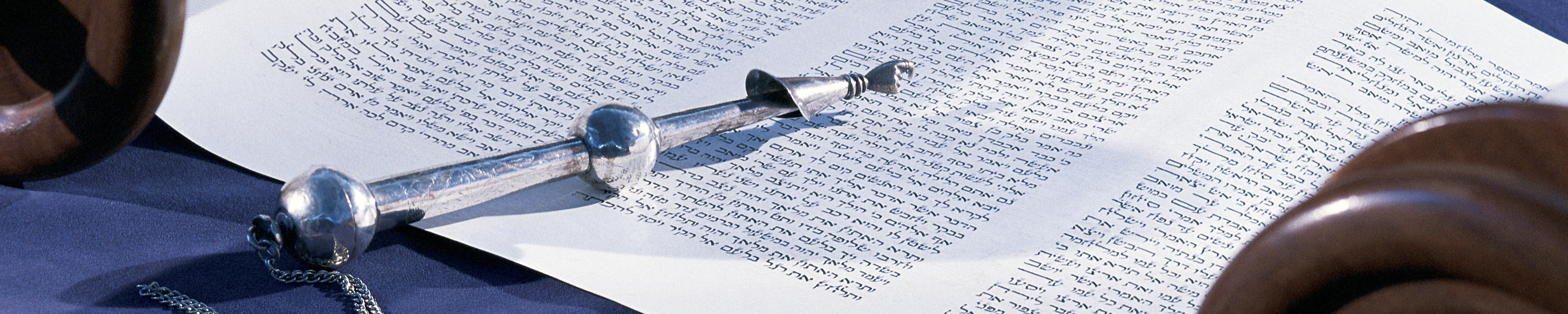

This is a question that jumps straight out of our parashah this week. In Parashat Va?eira, Moses asks Pharaoh to release the Israelites from bondage to worship God in the wilderness. When Pharaoh is stubborn, God sends a series of plagues, wondrous signs for Pharaoh, the Egyptians, and the Israelites to see. These signs are to prove God’s power and might, but more than that, they are to show that a refusal to follow God’s commands will result in pain and loss.

The third plague, lice, is telling. Pharaoh and the Egyptians have witnessed two plagues before: blood and the frogs. When God turns the Nile to blood, Pharaoh’s magicians do the same, and “Pharaoh turned and went into his palace, paying no regard even to this” (Exodus 7:23). The magicians are also able to replicate the frogs, though they are powerless to get rid of them once making them appear. But with the lice it is different. The magicians are unable to replicate the sign. They understand what they are witnessing. The magicians said to Pharaoh, “This is the finger of God!” (Exodus 8:15). But Pharaoh’s heart stiffened and he would not heed them.

The difference between the magicians’ response and Pharaoh’s response teaches us something important. Both see the same evidence for God’s power and presence, but each responds differently. The magicians see the lice, and they understand that God is more powerful than they. They connect completely with what their eyes are telling them. They are able to call it unequivocally what it is—this is God’s power, not ours. But Pharaoh refuses to believe what his eyes see. His heart stiffens.

How does that happen? Why do we refuse so often to believe what our eyes tell us? Why do we ignore what is so plain to see?

I believe the answer is that believing does not come from the eyes, but from the heart. Our eyes can witness all the evidence in the world, but unless the heart is willing to believe, then the evidence matters none.

Take, for example, Pharaoh’s response to the fourth plague. God brings swarming insects throughout the land of Egypt, laying the land to waste. The region of Goshen, where the Israelites live, however, is spared. God wants to show Pharaoh a distinction between his people and God’s people. So Pharaoh begins bargaining. First, he offers them the opportunity to worship within the land of Egypt. Moses explains that this won’t work, so Pharaoh seems to relent: “ ‘I will let you go to sacrifice . . . but do not go very far’ ” (Exodus 8:24). But when he sees that the swarms of insects have abated, he stubbornly refuses to let the Israelites go.

So long as the threat seems imminent, Pharaoh is willing to believe. But when the threat seems to have passed, he reverts back. He sees with eyes, but has not yet come to believe in his heart.

So often throughout history, we cannot make the connection between head and heart. We see a loved one succumbing to illness but refuse to believe it will be fatal. We hear stories of concentration camps and mass murder, but refuse to believe it will spread to our village. We are told time and again that we are despoiling our environment and causing climate change, and yet still there are those who say, “We don’t believe it.” We are taught from early childhood the dangers of cigarette smoking, and yet we ignore them.

We can, like Pharaoh, believe there is no God. We can believe that we have all the power, that there is nothing out there larger than we are. We can ignore all the signs we see all around us of a deeper sense of meaning and purpose to our lives. We can rationalize the power of human connection and spiritual empowerment. We can harden our hearts to what lies deep within ourselves and in the experience of life.

Or we can soften up a bit. We can open our hearts to the spiritual potential we find in the world, a spiritual power that asks us to create a unity between head and heart, between what we see and what we believe. We can let the connections we build between our heads and our hearts inspire us to act, to build healthier lives and a holier world.

Perhaps we do not have the immanent wonders that Moses brought before Pharaoh and the Israelites, but we have plenty of signs of our own that should be tugging at our hearts. And if we can learn to open our hearts to what God is trying to tell us, then we may find ourselves liberated from the plagues that afflict us in our age, and find our way forward to a brighter and better future.

Rabbi Dan Levin is the senior rabbi at Temple Beth El of Boca Raton, Florida.

Pharaoh’s inability to take to heart the lesson of the plagues is, as Rabbi Levin suggests, a powerful reminder that seeing is not necessarily believing. Alas, as the story of our liberation unfolds, it becomes painfully clear that the Israelites are equally blind to God’s presence. Miracles do not move us any more than they do Pharaoh. Much as his heart is hardened, our spirits are crushed. Thus, when Moses first performs portents, and proposes to bring us out of Egypt, we refuse to listen. Immediately after our miraculous passage through the Red Sea, we complain about the bitter water. Our response to the thunderous revelation at Mount Sinai is to ask Aaron to make us a Golden Calf. Indeed, in the entire Hebrew Bible, there is not a single case of a miracle inspiring in anyone a sustained faith in God. My teacher, Rabbi Herbert Brichto, z”l, argued that this is, in fact, the core lesson of miracles: Torah comes to teach that they are not grounds for spiritual living. We don’t believe on account of what we see; we see on the basis of what we believe.

So if miracles fall flat, what does constitute a firm foundation for a faithful life? David Foster Wallace tells the story of two young fish who are swimming along when they meet an older fish coming from the opposite direction. “Morning, boys,” he says, “How’s the water?” The two young fish continue along silently until eventually one of them looks at the other and asks, “What is water?”*

Wallace’s point is simple: the only way to open our hearts—and therefore also our eyes—is to live mindfully. What blinds the young fish—and Pharaoh and our own biblical ancestors and, of course, ourselves—is our tendency to operate wholly unconsciously, to take things for granted rather than making our choices consciously. Our challenge is, as Wallace notes, to keep reminding ourselves over and over: “This is water.” It all begins with mindfulness. Full consciousness is the real miracle.

*David Foster Wallace, This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009)

Daniel B. Fink is the rabbi of Congregation Ahavath Beth Israel in Boise, Idaho.

Va-eira, Exodus 6:2-9:35

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 420-448; Revised Edition, pp. 379–400;

The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pp. 379-400

Haftarah, Ezekiel 28:25–29:21

The Torah: A Modern Commentary, pp. 696-699; Revised Edition, pp. 401-404