It is a tree of life to those who hold fast to it, and all its supporters are happy. Its ways are ways of pleasantness and all its paths are peace.

-- Proverbs 3:18

Recently in my congregation, while holding fast to the Torah, we didn’t hold fast enough – literally – and it accidentally fell to the floor during a Shabbat service.

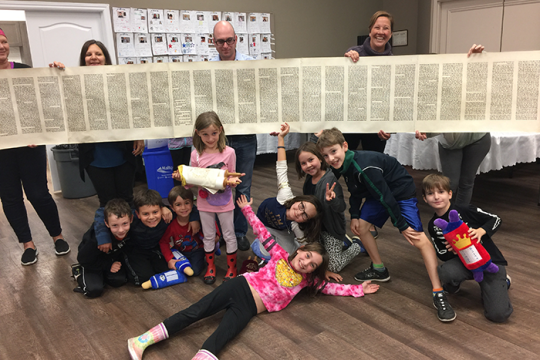

Such occurrences are rare, and fortunately the scroll did not sustain any damage. Still, Jewish tradition prohibits a Torah scroll from touching the ground – and it also provides us with a path toward restoring its sacred status when the prohibition has been breached. Known as a tikkun Torah (repair of Torah), the person who dropped the scroll and those who witnessed it are obligated to observe a minor fast (from morning until evening) for 40 days and perform some act of tzedakah (using money to do the work of world-repair or, literally, justice). Until then, the scroll cannot be used. (Had our Torah been damaged, we also would be required to have it repaired before using it again.)

The accident provided our entire community with an opportunity to respond as liberal Jews in the spirit of Jewish tradition, which is why 40 of us – 36 congregants and four clergy members – agreed to join together in a one-day, minor fast. (Most of us fasted a week ago Thursday, but a few will complete the requirement by Shavuot.) Fasting not only demonstrates respect for sacred Jewish objects, but also helps the community atone for having unintentionally dropped a Torah. That evening, many of us came together to break our fast and talk about the meaning of the day.

Here is some of what we learned from each other and our clergy during the discussion.

- The number 40 around this tradition of fasting – whether it is 40 days or 40 people – signifies both the years the Israelites wandered in the desert, and the days and nights Moses spent atop Mt. Sinai receiving Torah, our people’s most precious possession.

- For many of us, this fast day felt different, but no less meaningful, than our Yom Kippur fasts. To begin with, we all went on with our usual, daily business – work, meetings, childcare, and the like – although the fast generally was not far from our minds.

- The fast seemed to be a unique moment in Jewish time, and one – unlike on Yom Kippur, when we focus on our individual relationship with God – centered on community and the responsibility each of us voluntarily had accepted to help return a treasured Torah scroll to ritual purity. A few people noted that choosing to participate in this fast may prompt them to rethink the whys of their Yom Kippur fasts.

- Perhaps most powerful of all was the fact that the Torah itself didn’t change or move throughout the day. Rather, it was our action – individually and together in community with each other – that caused the change in its status. Indeed, it is we who possess the ability to restore our scroll from posul (ritually unfit) to kosher. By extension, it is up to us – and within our ability – to change, improve, and enrich ourselves and our communities wherever and whenever we see a need.

Tomorrow night as part of its erev Shavuot service, the congregation will formally acknowledge the change in status by rededicating the Torah scroll. I cannot think of a more fitting way to celebrate the Festival of the Giving of the Law, and I am proud and honored to have played a small role in making this rededication possible.

Chag Shavuot sameach!